I noticed recently that the RPGs that most reliably give me their intended experience, regardless of who I’m playing with or how experienced and familiar with the game the facilitator is, have an enormous amount of structure to them. At any given point, it is always clear in these games who is responsible for taking the next action and what their options are for that action.

A bunch of examples:

For The Queen: on your turn you draw a card, answer its prompt, and then optionally take questions from the rest of the group.

Dialect: on your turn you create a new word (or do something else allowed by the cards in your hand), then you frame a short scene around its use. You optionally feel out that process with the table. Additional precise procedures kick in to evolve the world between each go around the table.

Most Firebrands games: on your turn you pick a minigame and follow its instructions, which are detailed and particular in what options they allow and for who.

The Quiet Year: on your turn you draw a card, answer its prompt, follow any other instructions, and then choose one of three specific game actions. No one else speaks. At any time anyone may taken a Contempt token.

Microscope. Desperation. Even something like Fall of Magic, as open-ended as it is in the details of and manner in which you frame scenes, provides a clear structure and scaffolding for whose turn it is and what is expected of them on that turn.

You can even branch out in the OSR, or at least the post-OSR, for examples of games like this:

Errant is chock-full of tightly-controlled procedures, and it encourages you to add your own for whatever’s important to your table that it’s missed.

Barkeep on the Borderlands is a module about pub-crawling through a Mardi Gras style carnival with a pretty tight procedure for keeping the game moving. Everyone in the party takes one turn (it is left up to the group and referee to decide what that means, but my tables have fallen into an intuitive rhythm quickly) and then the referee rolls to see whether a random encounter occurs, everyone needs a new drink, or time passes. This keeps the story’s momentum forwards always at top of mind for everyone at the table.

Anyway, that was a smorgasbord of examples of the kind of tightly structured game I’m talking about here. They have turns, they have restrictions around what you’re allowed to do on your turn, and as a result they are in my experience remarkably consistent.

I adore this style of game. There’s nothing that kills momentum at the table for me more than everyone looking around and going “okay, now what?” If it’s not clear who is responsible for the next moment of play, or if it’s clear who but they haven’t been given any handholds for what to do with it, you’re fucked. People become paralyzed by choice and by the vastness of an empty page, infinite possibilities. Maybe not permanently, but this kind of moment is a huge speed bump on play.

Compare to D&D: when are you actually supposed to roll dice? What are you actually supposed to do next as a player and as a character? The game does not have great answers. At best, it has an implicit conversational procedure. At worst, it leaves you completely high and dry to figure all this shit out on your own.

Compare to an open-ended PBTA game like Apocalypse World or Dream Askew. These games give you mechanical signposts to steer into, and they otherwise trust you to carry on a conversation (or The Conversation). These tend to work great for me once they get rolling, but they also often leave my tables unsure how to get started or what to do next.

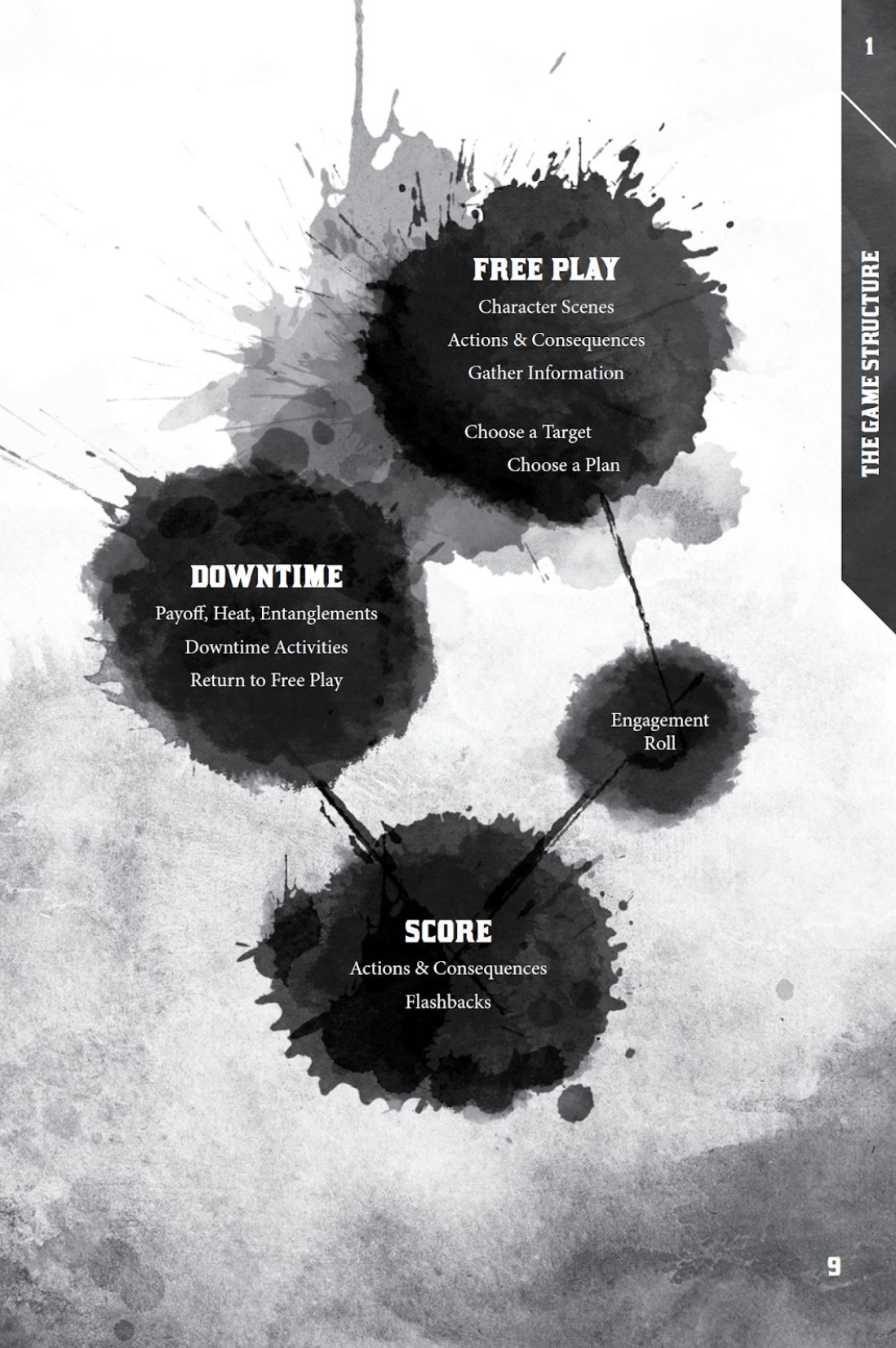

Compare to Blades in the Dark: the rules are heavily structured, forming a tight loop from scores to aftermath/entanglements to downtime and back to scores. But the game says there’s another phase in there, “free play,” between downtime and scores, where “characters talk to each other, they go places, they do things, they make rolls as needed” and “During free play, the game is very fluid—you can easily skim past several events in a quick montage; characters can disperse in time and space, doing various things as they please.” There’s even this chart from the game that implies free play should be like a third of play:

In practice, I see many tables skip over free play entirely, minimize it, or get confused what they’re supposed to do when they’re in it. Players gravitate towards the phases of play that are more structured. There’s nothing wrong with that style of play, but if you want something different, you have to push against the current and figure out how to do so for yourself.

In my experience, the learning curve in more open-ended games comes from getting a feel for when to actually engage with the rules and when to slip back out into just talking with each other. Games where the answer is clear and easy to remember tend to be my favorites, and games where you are never not in the middle of a procedure of some kind (even if that’s a Fiasco-style “play the scene out”) are the clearest and easiest to remember of all because there’s never any question about the answer.

Looser Procedures Demand Stricter Fiction

There is a circumstance under which games with very loosey goosey rules and procedures end up working fine for me: when the fictional world around them is heavily detailed.

When running modules written for games like Cairn, Mothership, and Mausritter, I find I almost never need to bring up mechanics. Instead of the rules of game making it clear what to do next, the fiction of the world serves that purpose.

There’s a whole argument here, that is I think both self-evident and worthy of its own book, about how procedural rules and truths about the fictional world aren’t meaningfully different in the way they frame the act of playing pretend with your friends. But I do see a trend in my tastes related to this: I really want at least one.

Meanwhile if there’s not much of either, it’s hard to grab onto anything and make a story happen. Taken to the extreme: not many people are out there just completely freeform making shit up with their friends.

In Conclusion,

Games that are super structured procedurally remove so much uncertainty from play and deliver the most consistent experiences. I think they’re best for people new to the hobby, and as a player I find that clarity reassuring myself.

The less structured your game is procedurally, the more I prefer it to be super specific fictionally. You gotta give me something to hang on to.

These highly-structured games are not the end-all-be-all of RPGs. Obviously. But I think this kind of game should be called out, appreciated, studied, and drawn from by more designers. Try a more tightly structured experience for your game during design and see what happens.